What is Russia like? It’s difficult to explain to people who have never been to a “second world country.” The West likes to paint Russia as a depraved place but in reality, it’s not that bad. It’s not like the wild wild west. It has nice parts and poor parts. It has problems but also extravagant luxury at times. The divide between rich and poor is outrageous in the US. But I feel like in Russia, it is an even wider gap. The rich control everything and regular people are left with nothing.

The city that I spent most of my time in while living abroad is Samara. I have so many mixed feelings about Samara. It is the ninth largest city in Russia, with a population of over one million. It is part of Western Russia but at least eight hours by train away from Moscow and St. Petersburg. It is on the banks of the Volga River.

Before coming to Samara, I had been told that it is the “San Francisco of Russia.” That’s one way of looking at it. The city is known for its embankment which sits on a downhill slope towards the Volga River. So I can… sort of… see it that way? The city comes alive in the summer. In the summer, it is certainly a place where people roller skate, lay out on the beach, barbecue, all that fun stuff.

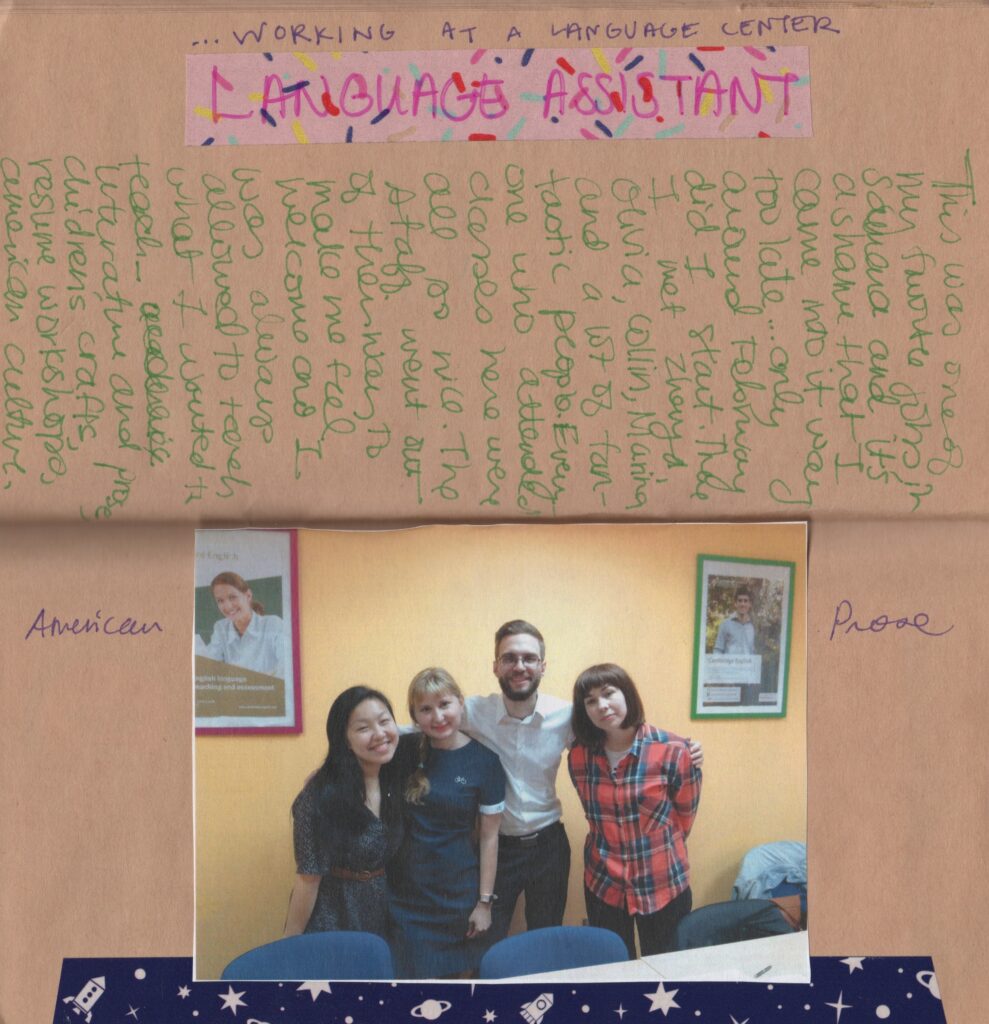

I lived in Samara for nine months. I had four different jobs. I worked full time as a university lecturer, part time at a private language center, part time at a local gymnasium (a fancy term for private school), and at a work and travel program. The university lecturer job was ok. The differences between American and Russian university students is pretty stark. For one, university is almost free. More people attend university in Russia than they do in the US. Because of that, there is a sense that it is high school 2.0. It is basically a requirement to go. It seems like the stereotype of people who do not go into university when they’re eighteen is that they go straight into the army. They also have a different culture of the army, that there is a higher concentration of recruits from poorer ethnic republics. Another aspect is that in the US, higher education is seen as necessary for job advancement and higher pay. In Samara, that was not the situation because wages are stagnated and a degree does not guarantee a good job, a high paying job, or even a job within the industry. I am aware those are not the outcomes in the US either, but there is more of a match. For example, in my college of education program in the US, every one of my peers became an elementary school teacher, whereas the pedagogy program I worked at in Samara, only a few students pursued that after graduation.

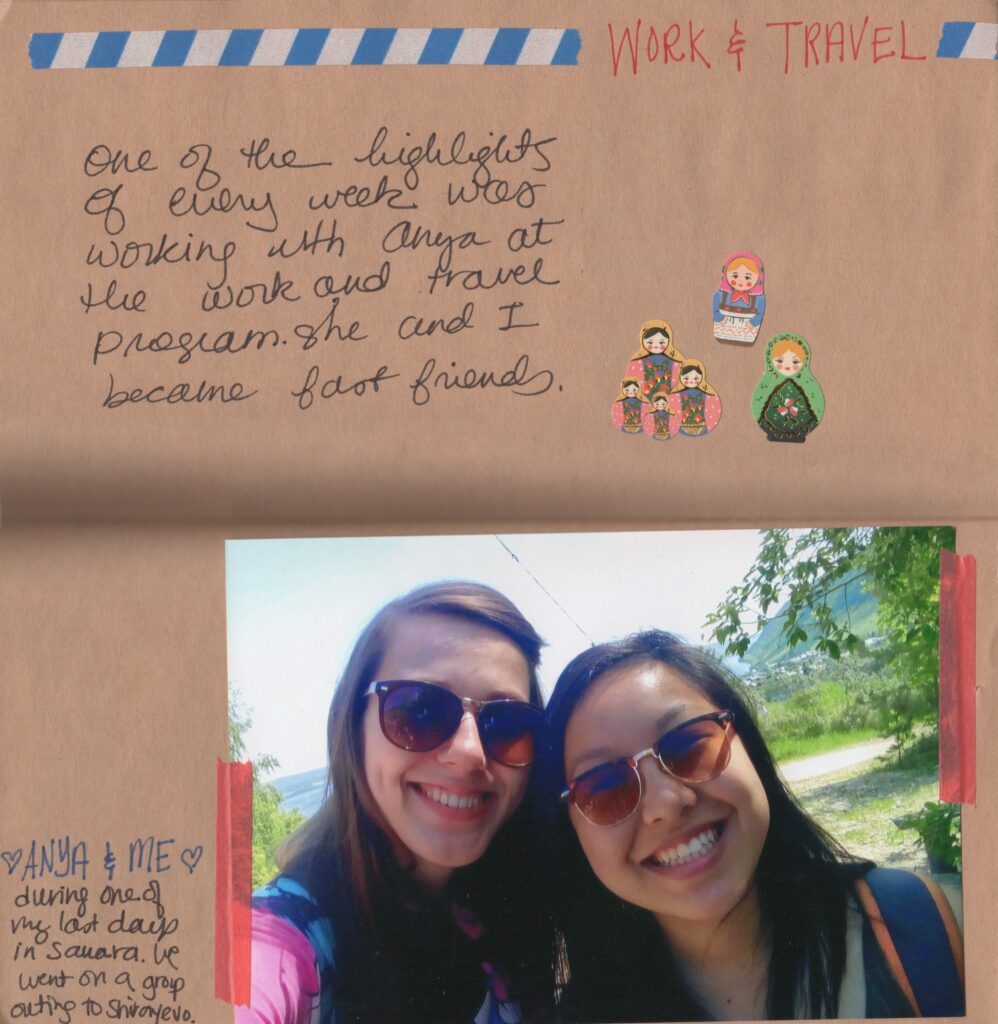

One of the better jobs I had in Samara was working at a work and travel program. Basically, many countries, such as Russia, have programs that help youth find temporary minimum wage jobs in the US. Often, these are roles in theme parks and stores. Many of my students ended up working in New York City, some in Ohio, some in Wisconsin. It was just what was available or what their other friends had connections at. If you ever wonder why there are so many foreign young people staffing theme parks, it is probably because they are taking a part of a short-term work and travel program. These programs try to get students visas to come work. Often, it is under an “illegal” tourist visa. Many students overstay their visa and never return to their home country. Conditions are pretty bad, and job prospects can be low, so it is understandable that some may not want to return. When I stayed in Turkey, I had also met people who had taken part of a work and travel program to the US.

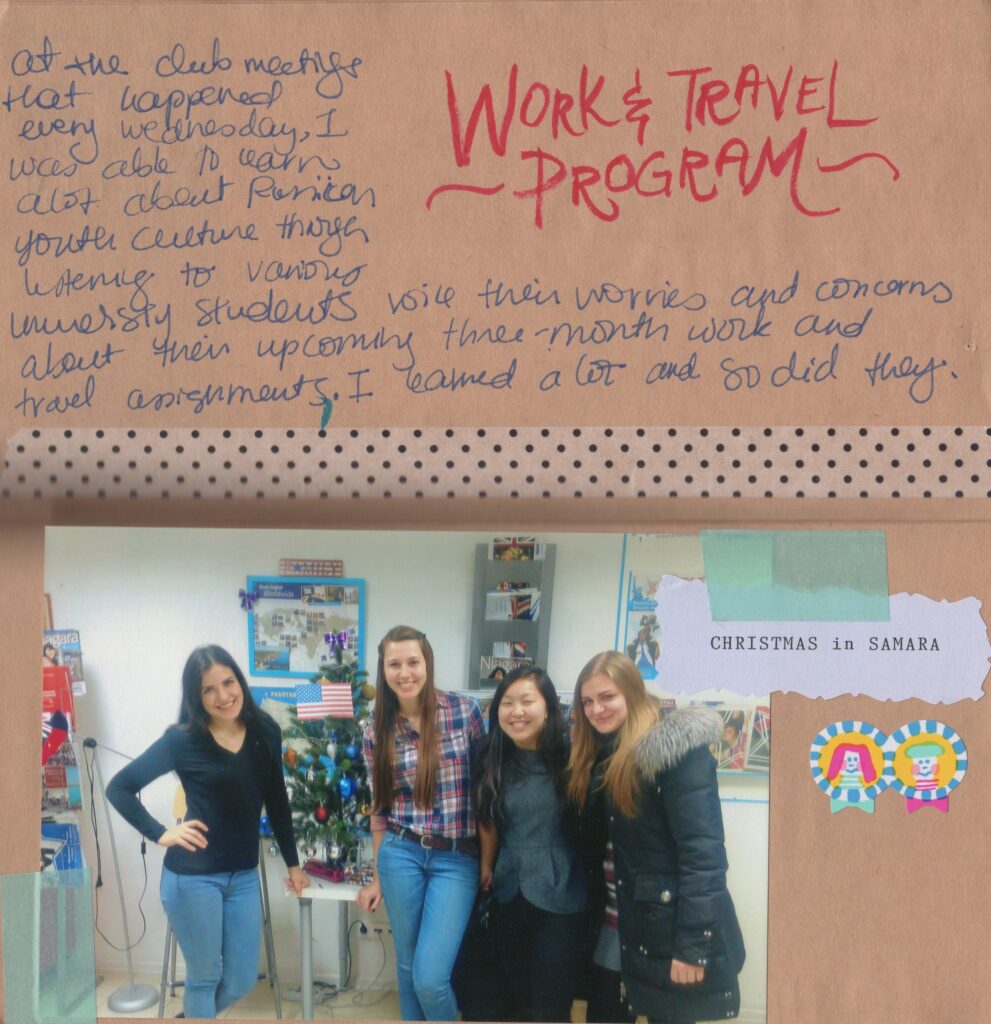

I held an informal English club at a work and travel center once a week. Students would come to prepare their paperwork and get ready for an English interview at the American embassy in Moscow. At every turn, there were so many ways Russian students would be turned around. For one, it is expensive to file for a visa. The paperwork is complex. They need to secure a job interview with the park, store, or restaurant, they intend to work. After that, they need to travel to Moscow, which is pretty expensive compared to travel in the US. Most students travel by train to Moscow and find friends to stay with, as hotels are also out of a typical Russian student’s financial means. They can pass all those steps but then fail their English interview at the American embassy. They might not show strong enough English skills. They might not make a convincing enough argument. They might cast doubt that they may not keep to their promise of returning home after the job assignment. It was tricky. At the club that I taught, my job was just to tell students about American culture. It was pretty fun.

A majority of the questions had to do with what was New York City like and had I ever been to the Statue of Liberty. Students also wanted to confirm of things they had seen in American movies were real – like Fourth of July being a big holiday or frat parties were a real phenomenon. I had never been to New York City prior to traveling to Russia, so I didn’t have much to offer. I told them a lot about Texas, though, but I don’t think I convinced any of them to travel there.

What is sad to me is that even after such a process, they will be earning below minimum wage at these American jobs. However, I met many happy students who returned summer after summer to work in the same parks. I also met students who stayed and are technically undocumented, cannot return to Russia. I feel like our countries could do better as providing short term jobs with higher pay. Or at least more specialized work. But as the US workplace is mostly monolingual, it’s difficult to think of other solutions.

I also became really good friends with the administrator of these work and travel English club meetings. We had a lot in common and I got to see her again when I visited Los Angeles. Even though Samara got to be dreary at times, I was happy to share traditions like Valentine’s Day and Christmas with young people.